日本研究及專書一覽

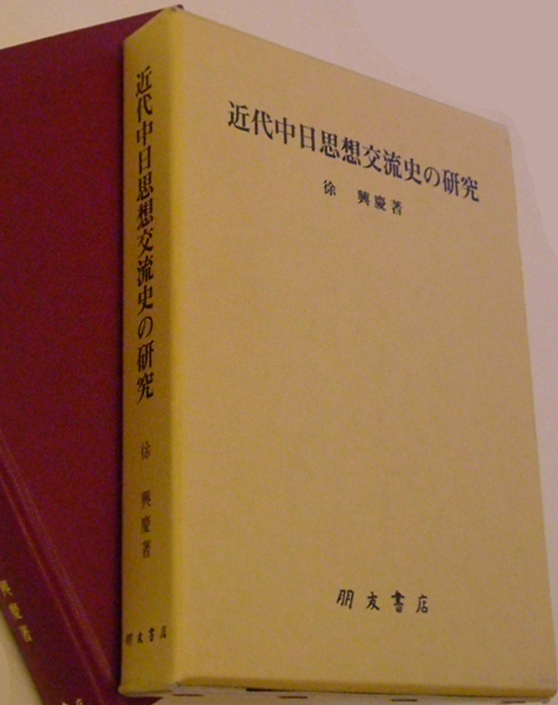

作者:徐興慶

出版社:朋友書店

出版日期:2014年2月

語言:中文.日文

ISBN:4892810959

中文摘要

近代中日關係史的領域中,有關文化及思想交流的研究,歷史長遠,內容更是豐富。十九世紀中期以降,在中日文化及思想交流的領域當中,有關兩國的啟蒙思想家們思考如何攝取西洋近代文明的研究,至今已有不少的成果。若以領域加以區別整理,大致可以分為人物、典籍以及思想交流三大類。這些先行研究當中,有不少評價很高,具參考價值的研究成果。但是不可諱言,在此類的研究範疇當中,因為受到相關原始資料難以發掘的限制,至今仍有許多值得深入探討的課題,無法突破。

本書從明末清初的戰亂到十九世紀西洋列強壓境中國的時代背景切入,探討近代中日文化及思想交流,時間從十七世紀中期的渡日儒者朱舜水(1600-1682)與中日文化交流開始,到 1840 年的鴉片戰爭,歷經 1850 年代的太平天國之亂,一直到晚清的知識份子為了攝取西洋新知,企圖改變傳統,將新潮的思想改革移入中國的變法維新到十九世紀末期,孫文的革命思想萌芽為止。與此時間點相互對照的日本,則含蓋前近代幕藩體制的鎖國時代,幕末的攘夷、倒幕、開國之混亂期,至明治維新初期為止。

這段期間,中日兩國因為西洋勢力的入侵,紛紛引發了危機意識。雙方在必須堅持傳統儒家思想的思維模式中,產生了汲取西洋文明的覺醒。面對這種矛盾的心理因素,中日兩國的思想家們對於國家未來發展的定位及價值觀產生了明顯的變化,因此兩國在政治、外交、軍事、教育、文化、思想的各種領域當中,有著複雜的交涉及掙扎的過程。在備受西洋文明威脅的東亞國際社會當中,晚清以及幕末、明治初期的日本,有為數不少的啟蒙思想家,為了國家的永續發展,開始思考如何從苦境的劣勢當中跳脫出來,他們期望自己的國家能獲得西方世界平等的對待。

在近代化過程中,雙方的思想家們不僅關心西洋文明知識的吸收,他們更將廢除不平等條約,以及走向富國強兵之道視為當務之急。這個認知即是當代中日兩國人物及思想交流的接點。

據德川幕府在長崎收集、編纂而成的『和蘭風説書』1840 年 7 月 1 日的記載,日本在得知英國集結本國及配置在美國、印度的軍隊,即將侵入中國的消息之後,幕府當局受到相當大的衝擊,引發他們抵禦西方列強的危機意識。從這個時期開始,將近有三年之久,日本幕府強制進入長崎港的荷蘭船及中國船都必須提出一份「海外事情報告書」,做為幕府掌握西方列強在東亞海域擴張勢力的參考資訊。

晚清在 1842 年 8 月鴉片戰爭失敗後,被迫與英國簽訂了不平等的南京條約,除割讓香港之外,廣東、廈門、福州、寧波、上海被迫開港,同時還支付了巨額的賠償金。這個消息傳入日本之後,一向奉中國儒教為圭臬的幕末思想家及幕府高層,難以相信儒教聖人的中國會敗給名不見經傳之西洋小國。因此,當西洋的勢力入侵東亞,日本也同時被捲入世界資本主義市場之後的數十年間,日本可以說目不轉睛地凝視著整個中國的動盪過程。

本書第一部以睌清思想家們所關注的實學理論對日本思想界的影響為主軸,首先探討鎖國時代流寓日本,曾被幕府副將軍德川光圀(Tokugawa Mizu Kuni,1628-1700)禮聘為國師的明末儒者朱舜水(Shu Shun Sui)對國家的認同問題,並針對朱舜水提倡經世致用之實學理論在日本幕末前期水戶學(Midogaku)的發展過程中所扮演的角色,以及他與當代日本的儒學界之思想交流內涵做了詮釋。另外,分析與朱舜水同樣提倡經世致用之晚清實學思想家魏源(Gigen,1794-1857)編纂的『聖武記』(Sebuki)、『海國圖志』(Kaikoku zushi)東傳日本之後,其主張的「師夷之長計以制夷」之禦侮思想如何影響佐久間象山(Sakumashouzan, 1811-1864)、橫井小楠(Yokoi ShouNan, 1890-1869)、吉田松陰(Yoshita ShouIn, 1830-1859)、高杉晉作(TaKaShugi ShinSaku, 1839-1867)等幕末思想家,本書以三章的篇幅分別論述中日思想變遷的相互影響及過程。

晚清被迫開港、賠償的遭遇,喚起了日本幕末、明治維新時期的危機意識,魏源倡議「師夷之長計以制夷」的主軸思想,即是日本用以應對西洋勢力入侵的執行方向之一。從鎖國、攘夷、倒幕至門戶開放,晚清的知識份子如何認知這段日本國策的修正與變遷,中日思想家們都陷入了攝取西洋文明與保留傳統的儒家思想,可否同時進行的苦思與抉擇。透過兩國知識份子的思想交流,闡明上述兩國互相認知與影響的思想變遷史,向來是中日及歐美學界極為重視的範疇之一。

本書第一部第二章,主要在分析晚清中英南京條約簽訂之後,全國政治、經濟、軍事、國防等改革陷入泥沼之際。魏源編撰『聖武記』、『海國圖志』闡述他對軍事、財政及國防等政策上應該推行的理念及實行的對策。論述的重點置於受到魏源思想影響的日本幕末思想家們,從海防架構的重組與省思、門戶開放與否的掙扎與改變、西洋「長技」文明之攝取與執行等不同的角度,思考日本救亡圖存的治國理念,並探究他們對於晚清中國的認知與思想之變遷。同時分析兩國知識份子在思想交流過程中,對西洋文明認知的異同問題。

鴉片戰爭以前,佐久間象山是篤信朱子學為正學的儒學家,但英國入侵晚清之後,西洋大砲的威力超乎中國與日本的想像。為提昇日本的海防戰力,他日以繼夜的學習荷蘭語,閱讀大量的西洋書籍,從蘭學運用的角度吸收西洋的科技及海防知識。中英南京條約簽定的三個月後,佐久間象山即向幕府提出「海防八策」的防禦理論。他建議禁止將銅輸出國外,以便鑄造大砲,又提議向荷蘭購買二十艘軍艦,並招聘荷蘭的兵學家、砲師及造船技工,列入幕府應該立即執行的急務。

佐久間象山批評晚清的腐敗,係固守陋習,輕視西洋為夷狄之邦,不知講求新知、改正弊端,更不知英國科技發達已凌駕中國之上,導致西洋勢力入侵中國得逞,此舉對以古昔聖賢、泱泱大國自居的中國而言,可謂體面盡失,他說這種恥辱貽笑世界。佐久間象山對晚清的腐敗觀察入微,批評犀利。

對於割讓香港、賠償鉅款,致晚清國勢一蹶不振,佐久間象山憂心這種連鎖反應將禍及日本,因此思考積極力行魏源倡議之海防思想。1853 年美國太平洋艦隊司令培理(Matthew Calbraith Perry 1794-1858)扣關日本,1854 年與日本簽訂「日美親善條約」之後,開放了下田(Shimota)及箱館(Hakotate) 兩港,同年八月與英國簽訂「日英親善條約」,十二月與蘇俄簽訂「日露親善條約」,結束了日本長達兩百餘年的鎖國及幕藩體制。面對西洋勢力快速的入侵日本,佐久間象山認為除了鞏固海防,加強戰備軍力之外,他以「學並東西,術兼文武」為職志。他所持的理由是,講究漢土之學難免止於空洞不切實際,而專學西洋之

術,則對崇高的道德議理學說之儒學精華會有失偏頗。他認為道德與技術缺一不可,否則所謂富國強兵皆是空談。因此,他創造出了「東洋的道德,西洋的藝術(技術)」融合東西文明的論點,引發了日本思想史學界廣泛的探討。佐久間象山讚佩魏源提出的「制夷」三部曲思想,他以「海外同志」認定了魏源的先見知之明,兩人同時異地的思考理論,確實存在著令人訝異的共鳴之處。

幕末思想家高杉晉作(Takasugi Shinsaku,1839-1867)是日本近代化過程的代表人物之一,他曾經在長州藩校「明倫館」(Merinkan)以及幕末知名的啟蒙思想家兼教育家吉田松陰主持之「松下村塾」(Shouka Sonjyuku)受過中國傳統的儒學及文化薰陶,漢學造詣亦有相當的素養。高杉晉作也是禮讚日本接受中國傳統文化教育的支持者,但他在晚清太平天國戰亂之際,奉派赴上海考察,目睹晚清腐敗的一面,記載了《遊清五錄》。這些日記對他向來崇拜的中華帝國之腐敗現象多所批評,隨處充滿著對中國的失望,導致他原來所持的中國觀有所轉變,他的言論也激發幕末日本產生了民族危機意識。高杉晉作並不只是一位倒幕派的先驅者而已,他可算是眾多幕末思想家當中,親身體驗日本從棄守封建體制到「開國」接納國際世界之變遷過程的人物,同時他也是在上海目睹東方與西方勢力衝突的見證人。更重要的是,他能跳脫幕府鎖國的保守巢臼,對前所未有的東亞情勢之變局,以國際的視野,呼籲日本思想界反思日本對傳統中華思想之定位問題。高杉晉作對尊王攘夷思想的主張,以及他的中國觀之演變,都具有劃時代的歷史意義。 本書第一部第三章除針對高杉晉作在「明倫館」及「松下村塾」接受中國傳統漢學教育之思想,與他日後倡議尊王攘夷思想的關聯性做一探討之外,並分析高杉晉作赴上海考察之經緯,論述他對中國認識之變遷始末,及其對日本幕末思想界的影響。

高杉晉作在日本近代化過程中,始終以尊王攘夷思想貫徹倒幕的目的,他反對門戶開放,而頑固、草莽又略帶前衛的行為思想,引發日本同時代思想界的震撼。高杉晉作對日本幕末世局之演變,嗅覺敏銳,有先見之明,其諸多行動看似有勇無謀,亦不乏失敗之處,但就倒幕到明治維新的演化過程而言,他的思想與行動自有其豐富的內涵。

高杉晉作在《遊清五錄》日記中,對晚清的諸多批判,無疑是提醒日本人對文明中國的儒家思想及傳統禮俗的認知須做修正。他認為西洋的軍器技術、天文、曆算之學優於中國及日本,應積極汲取新知並付諸行動,以免落人於後。他感嘆晚清為了平定內亂,引狼入室,藉外力入侵中國,摧毀國體與尊嚴。聖堂孔廟挪為英軍營區,這種忽視傳統的禮儀法度失調現象,讓晉作一度懷疑他接受儒家五倫價值系統的教育,是否出現了問題?也使他原先持有的尊華思想產生了動搖。換言之,晉作在幕末到明治維新的演化中,日本在重新構築東亞國際新局勢的未來體系裡,他扮演了一個改變日本人認知中國的角色定位。

1868 年明治政府成立之後,全面帶動了日本的近代化,並銳意調整對外政策以厚植國力。短短的十年之間,日本調整了日、韓關係,同時與晚清交涉「中日修好規約」之簽訂,以突破長期以來中日無外交關係的困境,並企圖恢復兩國貿易關係,以改善明治政府日益惡化的財政問題。這段期間,日本不但解決了棘手的琉球問題,它還出兵台灣,從國際社會輿論的焦點與結果看來,表面上明治政府似乎人、財兩失,但是「台灣事件」,卻種下二十年後,日本覬覦台灣的潛在因素。從整個明治政府一連串對外政策的推動,不難看出其目的是在逐步打破自古以來中國所建構的「中華秩序」之朝貢體制。

明治四年(1871),日本派遣以岩倉具視(Iwakura Tomomi,1825-1883)為首的龐大使節團赴歐考察西洋文明,創下了修改不平等條約的先例,也落實了明治政府汲取西洋文明的政策。

睌清也在光緒 2 年(1876)派遣了駐英大使郭崇燾(1818-1891),1877 年派遣何如璋(1838-1891)出使日本,隨後也展開與美、俄、德、法等國的外交關係。隨著駐日公使館的設立,除了政治與外交問題彼此有直接的管道溝通之外,中日兩國的人物往來日益頻繁,雙方的文化與思想交流,亦有別於幕末的鎖國背景,無論深度與廣度,都突破了前時代的限制,也改變了晚清知識份子對日本社會的認知。

本書第二部份,以 1874 年晚清與日本建立外交關係為起點的人物及思想交流為探討主軸。第一章分析「中日修好規約」簽訂之後,雙方展開人物交涉的歷史意義。以筆者在日本長崎(Nagasaki)縣立圖書館發掘的第一手資料「日•清往復外交書翰文」,分析晚清江浙的陳福勳、馮峻光、沈秉成等地方官與明治初期日本的外交官柳原前光(1850-1894)、駐上海總領事井田讓、商務官品川忠道等人的交往過程。同時分析日本對晚清洋務運動的情報蒐集之經偉。

第二章針對 1873 年,明治日本出兵台灣的「台灣事件」,晚清總理事務衙門及地方官員的應對政策,探討當時國際社會及媒體的反應,並分析「台灣事件」之後,中日雙方的變遷關係。

第三章以 1877 年晚清的駐日公使館開館之後為時代背景,探討何如璋、黎世昌(1837-1898)、楊守敬(1839-1915)等晚清駐日外交官在日考察之內容與得失。他們都有以下的共同點,一為三人都是接受中國傳統儒教文化教育的晚清官僚,二是三人皆為晚清對日外交的前鋒人員、官方代表。他們也是明治初期第一批踏入日本,調查或見證過日本政治、社會近代化的諸相,同時也是直接與日本知識分子交流的日本研究集團。本文藉《使東述略》、《日本訪書志》等相關文獻,分析近代中日兩國人物在思想交流上的異同現象,同時也藉由學界很少利用的《清客筆談》,論述楊守敬將失佚已久的古籍珍本從近代日本回流中國的典籍交流之歷史意義。

第四章以睌清駐日外交官黃遵憲(1848-1905)對日本明治維新之思想受容的認知問題,分析他與當代日本文人在思想交流的內涵與成果,以及他完成《日本國志》後,中日朝野對該書所評價的歷史意義。另外,針對「中日修好規約」批准換約後的琉球問題談判,以及馬關條約所延伸的杭州、蘇州的治外法權問題,探討黃遵憲的對日外交主張。

第五及第六章,以 1899 年前後的戊戌維新期,穿梭在中日朝野之間,擬架構兩國新關係的政界邊陲人物•廣東豪商劉學詢(1855-1935)為中心,分析他赴日考察,與明治日本政商界交流所牽涉的睌清保守派、改革派對日政策變遷及人物交流的實況。同時探討「兩廣獨立」的歷史事件中,在李鴻章、孫文及當代相關的日本朝野人士的交涉過程中,劉學詢所扮演的角色定位。

英文摘要

The cultural and intellectual exchange topics in the field of modern Sino-Japan relationship are prolific and have been well-discussed. In particular, the studies on how enlightened thinkers in both countries from mid-nineteenth century on mulled over the assimilation of modern Western civilization have produced fruitful results. If classified by fields, those literatures may be divided into three categories – people-to-people exchange, literary exchange, and intellectual exchange. Quite a few of those prior studies received high remarks and offer reference values. But it should also be pointed out that in this type of studies, many topics that warranted in-depth discussion often lacked breakthrough due to the constraint of inaccessibility to relevant original data.

This book explores the cultural and intellectual exchange between China and Japan against the backdrop of warring chaos during late Ming and early Ch’ing Dynasty up to the time of Western encroachment on China’s territory. The duration spans from the time the noted Confucian scholar Zhu Shun-shui (1600 – 1682) on political exile in Japan, through the 1840 First Opium War, the Tai-Ping Rebellion in the 1850s, and to late Ch’ing during which the intellectuals learned new knowledge from the West and attempted to transplant the new waves of Western thinking and ideologies into constitutional reform and modernization, up to late nineteenth century when the revolutionary ideas of Sun Yat-sen sprouted. The events in Japan across the same time span include the period of national isolation under the early modernshogunate system, resistance against foreign intrusion in the twilight of Tokugawa era, the downfall of shogunate, the chaotic period in the early Meiji government, and the early stage of Meiji Reformation.

Over this time period, both China and Japan developed a sense of crisis in the face of encroachment by Western powers. Both countries were also awakened to the need to draw on the strength of Western civilization, while insisting on keeping the traditional, Confucian mode of thinking intact. In the midst of such conflicting mindsets, the views of Chinese and Japanese thinkers on the directions of their country’s development and sense of value underwent marked changes. The complexity of the issues and constant struggles were reflected in the arenas of politics, foreign affairs, military affairs, education, culture, and ideology of both countries. At the time the East Asian societies were under substantial threat from the Western civilization, a significant number of enlightened thinkers in China (late Ch’ing) and Japan (late Tokugawa period and early Meiji period) began to ponder over how to lift their country out of agony of inferiority and put the country on the path of sustained development and equal footing with the Western world.

In the process of modernization, thinkers of China and Japan not only were concerned about the absorption of Western civilization and knowledge, they saw more pressing issues in abolishing the unequal treaties concluded with foreign powers and moving the country on way to prosperity and military might. This awareness was the contact point in the exchange between Chinese and Japanese intellects at that time.

According to the account dated July 1, 1840 in the “Dutch Reports to the Shogunate” compiled by the Tokugawa shogunate at Nagasaki, the news of Great Britain amassing armies from homeland and troops deployed in America and India and ready to invade China sent shock waves through the shogunate regime, evoking in them a sense of crisis to fight off Western powers. For three years since then, the Tokugawa shogunate required all Dutch ships and Chinese ships that sailed into theNagasaki Port to submit a foreign report. The shogunate used information provided in those reports to grasp the state of expansion along East Asian seas by Western forces.

Following the defeat in the First Opium War in August 1984, the Ch’ing court was forced by the British to accept the unequal and humiliating Treaty of Nanking. By this treaty, the island of Hong Kong was ceded to Britain and five ports, Guangdong, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningpo and Shanghai were opened. The Ch’ing government also paid huge sum of indemnity. When the news reached Japan, thinkers and leaders of the shogunate who faithfully looked up to the teachings of Confucianism for guidance had a hard time swallowing the fact that China with her Confucianism and sages was dealt with humiliating defeat in the hands of a little-known Western state. Thus in the next few decades with the aggression of Western powers in East Asia and Japan’s own involvement in the world capitalistic markets, Japan watched the entire process of turmoil inflicting across China with rabid attention.

Part One of this book focuses on the influence of shi xue (Practical Learning) promoted by some philosophers and scholars in late Ch’ing on the intellectual community of Japan. This part sets out to examine the viewpoints of late Ming Confucian scholar Zhu Shun Shui on national identity (Zhu was once appointed by lieutenant general Tokugawa Mizu Kuni (1628-1700) as government advisor), the application of shi xue to governance advocated by him, and the role his shi xue theory played in the development of Midogaku (Mito School) in the early stage of Tokugawa shogunate, and his interpretation of the intellectual exchange with the Confucian scholars in Japan at that time. This part also analyzes how the extraordinary books (Military Campaigns of Great Emperors and Illustrated Gazetteer of the Maritime Countries) of Wei Yuan (1794 – 1857), a Chinese scholar of late Ch’ing Dynasty who, like Zhu Shun Shui, also advocated the application of practical learning to governance, and how his proposition of “mastering the superior techniques of foreigners to defeat them” affected the thinkers in the late Tokugawa shogunate, including SakumaShouzan (1811-1864), Yokoi ShouNan (1890-1869), Yoshita ShouIn (1830-1859), and TaKaShugi ShinSaku (1839-1867). Three chapters in this book are devoted to discussing the vicissitude of ideas and philosophy of Chinese and Japanese intellects and their mutual influence on each other.

The events in China, including forced port opening and payment of indemnity aroused a sense of crisis in Japan. The central ideas behind Wei Yuan’s “mastering the superior techniques of foreigners to defeat them” became one of the guidances Japan followed to fend off foreign forces. From the period of national isolation, resisting foreign aggression, downfall of shogunate, to the open-door policy, how did the intellectuals in late Ch’ing perceive the modification and evolvement of Japan’s national policies? That was also the time when both Chinese and Japanese thinkers went through long and hard thinking as to whether it was possible to accept Western civilization while preserving the traditional Confucian teachings. How the intellects in China and Japan perceived and influenced each other through intellectual exchange? The chronicle of changes to their mentality and attitude have been a topic the academic communities in China, Japan and the Western world paid considerable attention to.

The second chapter of Part One of this book describes the writings of Wei Yuan (mainly Military Campaigns of Great Emperors and Illustrated Gazetteer of the Maritime Countries which elaborated his beliefs in military, fiscal and defense policies and his propositions) when China’s reforms in politics, economy, military and defense were descending into quagmire in the aftermath of the Treaty of Nanking. The focuses are on how Japanese thinkers who were influenced by Wei Yuan’s propositions juggled over the restructuring of maritime defense, adoption of open-door policy, assimilation of the superior Western technology, and implementation as they contemplated ideas in governance that could secure the country’s survival. The second chapter also explores their perceptions of China in late Ch’ing and the transformation of their thoughts as well as the similarities and differences in the perceptions of Western civilization between the intellectuals of China and Japan during the course of intellectual exchange.

Prior to the First Opium War, Sakuma Shouzan had been a Confucianist and a devout believer in the Zhu Zi orthodoxy. But after the British encroachment into China which demonstrated the military power of the West simply beyond the imagination of both China and Japan, he began a relentless pursuit of Western knowledge, learning the Dutch language day and night and reading prodigiously Western books with the desire to absorb the Western science and technology and maritime knowledge. In three months following the conclusion of the Treaty of Nanking, he proposed to the shogunate a defense theory entitled Eight Tactics of Maritime Defense. He suggested banning the cooper export so Japan could build canons. He also suggested purchasing twenty warships from the Netherlands and recruiting Dutch military experts, artillery experts and naval architects as pressing issues that should be put to action by the shogunate immediately.

Sakuma Shouzan criticized the Ch’ing court of corruption, obstinately holding onto undesirable customs, condescending to the Western states and branding them the barbarians, ignorant in acquiring new knowledge, remedying fraudulent practices, and recognizing the superiority of British technology. He surmised that those faults brought Ch’ing Dynasty the encroachment of Western powers and grievously humiliating defeats, and such degradation exposed China, a great country known for ancient sages and men of virtues, to ridicules. The sharp criticisms of Shouzan demonstrated his keen observation of the corrupt state of late Ch’ing court.

Watching the slump of late Ch’ing court after the cession of Hong Kong and paying Great Britain huge-sum indemnity, Sakuma Shouzan worried that such chain reaction of calamities would ripple to Japan. So he mulled over putting the maritime defense advocated by Wei Yuan to practice. In 1853, the warships of the US East India Squadron, commanded by Commodore Matthew C. Perry (1794 – 1858) entered the Japanese port. In 1854, Japan signed the Treaty of Peace and Amity (Treaty of Kanagawa) and opened the ports of Shimota and Hakotate (today’s Hokkado). Similar treaties were concluded with Great Britain and Russia the same year. It signaled the end of the isolationist foreign policy and shogunate system that had been in place for over two hundred years. In the face of rapid advance of foreign powers into Japan, Sakuma Shouzan championed shoring up maritime defense and combat readiness. He also made it his personal mission to “learn the knowledge of the East and West, and master in civil and military techniques.” He maintained that over emphasis on learning the authentic Han teachings might border on being hollow and impractical, but exclusive learning of Western science and technology might be biased against the essence of Confucianism which stresses high morality and ethics. In his views, both morality and technology were indispensable in the building of national wealth and military might. Thus he proposed the theorem of “Eastern morality and Western art (science and technology)” which invited extensive discussions in Japan’s intellectual community. Sakuma Shouzan lauded Wei Yuan’s three-part thinking to “fend off foreign aggression” and affirmed Wei’s foresight in his writing of “Overseas Comrade.” The theorems conjured by these two thinkers at different places displayed surprising resonance.

Takasugi Shinsaku (1839-1867), a thinker in the late Tokugawa shogunate, was one of the representatives in Japan’s modernization process. He was nurtured in traditional Chinese Confucianism and culture at the School of Merinkan in Nagasu Machi and the School of Shouka Sonjyuku under the tutelage of Yoshita ShouIn, the noted enlightened thinker and educator in late Tokugawa shogunate. Takasugi Shinsaku used to be a trumpeter and supporter of traditional Chinese culture and education. But during his tour of Shanghai in the midst of Tai Ping rebellion, he witnessed first hand the decadence of late Ch’ing court and documented what he saw in the “Travelling Log of the Ch’ing Country.” In his journal, words of criticism and disillusion over the rampant corruption in the Chinese Empire, a country he had always revered, abounded. His views on China changed, and his opinions evoked a sense of national crisis in Japan. Shinsaku was not merely a harbinger in the overthrow of Tokugawa shogunate, he was, among his many contemporary thinkers, a personage who experienced first hand the process of Japan’s transformation from a feudal system to opening the country and admitting the outside world. He was also a witness in Shanghai to the confrontation between the Eastern and Western forces. More importantly, he could see through the conservatism of shogunate hiding behind the isolationist policy, and with international vision, called for the repositioning of traditional Chinese thinking. Shinsaku’s propositions of “reverence for the Emperor and the expulsion of foreigners” and the changing of his China outlook had an epochal sense of historical significance. The third chapter of this book examines the correlation between the thinking of Shinsaku during his years of schooling receiving the training of traditional Han School, and his later thinking advocating “reverence for the Emperor and the expulsion of foreigners.” This chapter also analyzes the experience of his tour in Shanghai, and discusses his changing perceptions of China and his influence over the intellectual community of Japan during the late Tokugawa shogunate.

In the process of Japan’s modernization, Shinsaku had steadfastly stuck to the belief in “reverence for the Emperor and the expulsion of foreigners”, and based on it, called for the overthrow of shogunate and took exception to open-door policy. His stubborn, ruthless, yet somewhat avant-garde behaviors and thinking rattled his contemporaries. Shinsaku had a keen sense of the development of world situation and foresight. Many of his actions seemed tactless and quite a few resulted in failure. But from the overthrow of shogunate to Meiji Reformation, his thoughts and actions in the process embodied rich substance.

The many criticisms of Shinsaku over the late Ch’ing court in his journal, the “Travelling Log of the Ch’ing Country”, were meant to remind the Japanese to modify their perceptions of the Confucian thoughts and traditional customs in the Chinese civilization. He reasoned that Japan should actively absorb new knowledge and put what was learned into action because the Western artillery technology, astronomy and mathematics were superior to those of China and Japan. He lamented that the Ch’ing court invited in dangerous foes for the sake of squashing internal insurgence and destroyed the state system and national prestige in the process. Witnessing that the reverent Confucius temple was allowed to be turned into camp for the British army, Shinsaku doubted for a while about the value system of five Confucian relationships he had been taught about and his reverence for China was also shaken. In other words, in Japan’s evolvement from the downfall of shogunate to Meiji Reformation and in the process of Japan’s reconstructing its position in the East Asian communities, Shinsaku played the role of changing the Japanese perceptions of China.

Since its establishment in 1868, the Meiji government embarked on modernization in full force and overhauled its foreign policy with the aim to build solid national power. In one short decade, Japan adjusted its relations with Korea and signed the Sino-Japan Cordial Relationship Agreement with the Ch’ing court to normalize its diplomatic relations with China. Japan also attempted to restore trades with China to address the increasingly deteriorating fiscal problem of the Meiji government. During this period, Japan not only solved the thorny issue of Okinawa, it also dispatched troops to Taiwan. From the perspectives of international opinions and the immediate outcome of its actions, the Meiji government seemed to have lost badly. But the “Taiwan incident” planted the seed for Japan’s lust for Taiwan twenty years later. From the successive foreign policies the Meiji government pushed forward, it is not hard to discern that it intended to break the imperial tribute system constructed by China under the scheme of “Chinese order” since ancient times.

In the fourth year of Meiji regime (1871), Japan dispatched a huge delegation of diplomatic envoys headed by Iwakura Tomomi (1825-1883) to Europe to learn more about Western civilization. This grand tour resulted in the modification of unequal treaty signed by Japan and put into effect the policy of Meiji government to draw on the strength of Western civilization.

The Ch’ing government also appointed Guo Chong-Xi (1818-1891) as ambassador to Great Britain in 1876, assigned He Ru-Zhang as China’s ambassador to Japan in 1877, and subsequently developed diplomatic relations with America, Russia, Germany and France. With the setup of an embassy in Japan, China and Japan established a direct channel of communication for political and diplomatic issues. The visits between the two countries became more frequent. Differing from the time of national isolation in the late shogunate period, the cultural and intellectual exchange between the two countries expanded substantially both in depth and breadth, which also altered the perceptions of late Ch’ing intellectuals towards the Japanese society.

Part Two of this book focuses on the people-to-people and intellectual exchange between China and Japan following the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1874. Chapter one of Part Two examined the historical significance of association and contact between the people of two countries after the conclusion of Sino-Japan Cordial Relationship Agreement. Based on the first-hand information the author discovered at the Nagasaki County Library on diplomatic correspondences between Japan and Ch’ing court, we will analyze the contacts between local officials of the Ch’ing court, including Chen Fu-xun, Feng Jun-guang, and Shen Bing-chen, with Japanese diplomats of early Meiji government, including diplomat Yanagi Sakimitsu (1850 – 1894), Japan’s consul general to Shanghai Ita Yuzuru, and commerce counselor Shinagawa Tadamichi, and Japan’s intelligence gathering on the Westernization Movement in China during late Ch’ing.

The second chapter of Part Two discusses the response policy of the Ch'ing State Council and local officials to the Taiwan Incident, and the reactions of then international society and media, and discussed the vicissitude of relationship between the two countries afterwards.

Chapter three of Part Two explores the findings and accomplishments (and misses) of Ch’ing diplomats, in particular He Ru-Zhang, Le Shi-Chang (1837-1898) and Yang Shou-Jing (1839-1915) during their residence in Japan after the Ch’ing court established its embassy there. Those three diplomats shared some common grounds, namely they were all late Ch’ing bureaucrats who had received the traditional Confucian education and they were the vanguards and official representatives of the Ch’ing court in Japan. They were among the first batch of Chinese who entered Japan in the early Meiji regime and had the chance to investigate or witness different facets of Japan in its political and social modernization efforts. They also comprised the Japan study group that had direct contact with the Japanese intellectuals. Through literary and historical documents – Shi Dong Shu Lue and Ri Ben Fang Shu Zhi, we will discuss the similarities and differences in ideas and philosophy between the Chinese and Japanese. Through a rare reference book – Qing Ke Bi Tan, we will examine the historical significance of Yang’s bringing back to China the missing ancient books and rare editions.

Chapter four analyzes the content and accomplishments of Chinese diplomat Huang Zun-Xiang (1848 – 1905) during his intellectual exchange with Japanese literary men based on his perceptions of the Meiji Reformation, and the historical meaning of evaluations he received from the Chinese and Japanese governments and the public after he finished the book – History of Japan. The chapter also examines the stands of Huang on China’s negotiation with Japan over issues of Okinawa and extension of Japan’s extraterritorial rights to Hangzhou and Suzhou derived from the Treaty of Shimonoseki.

Chapters five and six centered around Liu Xue-Xung (1855 – 1935), a wealthy merchant from Guangdong and fringe figure in the political scene who shuttled between China and Japan around the time of Reform Movement of 1898 with the ambition to build the new Sino-Japan relationship. We will analyze his interactions with politicians and businessmen in Meiji Japan in the context of disparate Japan policies proposed by conservatives and reformists of the Ch’ing court. We will also examine the role played by Liu in the process of negotiation conducted by Lee Hung-Zhang and Sun Yat-sen with their Japanese counterparts in the historical event of “independence of Guangdong and Guangxi.”

目次